Return to the main conference page.

Sinification, Globalization or Glocalization?: Paradigm Shifts in the Study of Transmission and Transformation of Buddhism in Asia and Beyond

Jackson Macor (University of California, Berkeley)

2024-01-25

The international conference “Sinification, Globalization or Glocalization?: Paradigm Shifts in the Study of Transmission and Transformation of Buddhism in Asia and Beyond” was held between August 9–12, 2023 at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). It was one of three parallel conferences as part of the inaugural forum “Beyond Civilizational Clash: Buddhist Perspectives on the Coalescence of Human Civilizations” hosted by the HKU Centre of Buddhist Studies. The conference was sponsored by the Glorisun Charity Foundation, and administered by the Glorisun Global Network for Buddhist Studies and From the Ground Up: Buddhism and East Asian Religions (FROGBEAR) at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Papers were presented both in English and Chinese by scholars from across Asia as well as Europe and North America. While the majority of presentations focused on issues in the study of Buddhism in China specifically, talks were also given on the role of Sinitic Buddhism in Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia, as well on the thematic issues of transmission and adaptation in Indian and Central Asian Buddhism. The conference primarily consisted of three panels on August 10 and six panels on August 11 organized according to both topical and disciplinary considerations. Talks were presented on a variety of issues, such as textual and doctrinal studies, art history, politics, archeology, and so forth. The event was also part of the 2023 Glorisun International and Intensive Program on Buddhism, a program that trains young scholars of Buddhist Studies from across the world with lectures and seminars given by leading Buddhologists and Sinologists from multiple distinct academic backgrounds.

DAY 1 (AUGUST 10)

The diversity of topics discussed at the conference was represented from the very beginning by the three keynote speeches chaired by Guang Xing 廣興 (HKU) that inaugurated all three conferences. Eugene Wang 汪悅進 (Harvard University) discussed several art historical issues in contemporary East Asia, Todd Lewis (College of the Holy Cross) focused on the transcultural historiography of Buddhism with a lens on South Asia, and Robert Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) discussed the philosophy of time as reflected in Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma.

The first panel of the conference proper was titled “Sinification of Buddhism, Again: Big Picture and Individual Cases,” and was chaired by Baba Norihisa 馬場紀壽 (University of Tokyo) with Chen Zhiyuan 陳志遠 (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) serving as discussant. Six papers were presented. The first given in English by Guang Xing 廣興 (HKU), titled “Sinification of Buddhism: A Philosophical Enquiry,” focused on what he called the “liberal attitude of mind” shared by both Confucianism and Buddhism. He argued that this shared set of values contributed to the willingness of the Chinese to accept Buddhism such that it could be integrated into Chinese culture.

Prof. Guang Xing

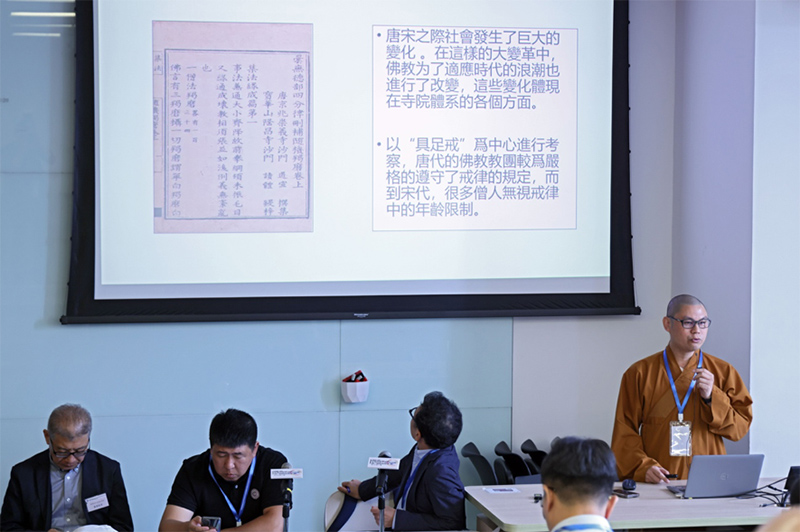

The next, given in Chinese by Sun Yinggang 孫英剛 (Zhejiang University), was titled “中古中國與犍陀羅文明 | Gandharan Buddhism and Medieval China,” and focused on the ample connections between China and Gandhara during the medieval period on the basis of textual, political, and art historical evidence as a way to illustrate the openness of Chinese civilization during the first millennium. The third presentation, titled “佛教中國化與漢傳佛典翻譯——以‘譯場’為中心 | The Sinicization of Buddhism and the Translation of Chinese Buddhist Classics: Centered on the ‘Translation Workshop,’” was given by Zhao Dinghua 趙錠華 (Hong Kong Chu Hai College) in Chinese. Zhao illustrated the importance of the complex proceedings that occurred in the process of translating Buddhist texts into Chinese for the assimilation of Buddhism in China. The next presentation, “佛經傳譯對漢字形成的影響——以‘魔’字為例 | The Influence of Buddhist Scripture Translation on the Formation of Chinese Characters: Taking the Word ‘Mo 魔’ as an Example,” was delivered by Chen Yingjin 陳映錦 (Beijing Language and Cultural University) in Chinese, who highlighted the philological issues in the origin of the Chinese character mo 魔 and its disputed origins in the translation of Buddhist texts. The fifth presentation, titled “唐宋受戒狀況變化之考察 | The Transforming Ordination Practice During the Transition from the Tang to the Song Dynasty,” was given in Chinese by Shi Daowu 釋道悟 (Mount Kuaiji Institute of Advanced Research on Buddhism), who demonstrated that while the minimum age for full ordination calculated by the Vinaya expert Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667) was generally followed during the Tang 唐 (618–907), it had come to be disregarded by the Northern Song 北宋 (960–1126), signaling a transformation of Buddhism at the societal level.

Ven. Daowu

Ven. Daowu

The final presented given by Zhao Wen 趙文 (Nankai University) in English, “The Indigenous Interpretation of Core Concepts in Early Chinese Translations of Prajñāpāramitā Literature,” examined the critical influence of the earliest Chinese translation of the Prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of Wisdom) scriptures, the Daoxing jing 道行經 [Sūtra on the Practice of the Way], on the tenor of Buddhist thought during the Western 西晉 (265–316) and Eastern Jin 東晉 (317–420) dynasties through case studies of the translation of key terms of art such as tathatā, asvabhāva, dharmadhātu, etc.

The second panel, “China vs. Japan and Korea,” was chaired by Shen Weirong 沈衛榮 (Tsinghua University), who also offered comments alongside Pei Changchun 裴長春 (Shangdong Normal University). Three presentations were delivered in English and one in Chinese, focusing on two cases in Japan and two in Korea. The first by Ashiwa Yoshiko 足羽與志子 (Hitotsubashi University/National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies), “Contemporary Intercultural Interactions between China and Japan as Seen through the Obaku Sect,” focused on the unique ties of the Ōbaku sect 黄檗宗, the final sect of Japanese Buddhism imported from China in the seventeenth century, to modern China as a case study in the overseas expansion of Buddhism from the People’s Republic of China. The second presentation, in Chinese, titled “中日天台宗師僧齋忌儀式文本:從智顗‘霜月會’談起 | Memorial Ritual Texts of Tiantai/Tendai School Masters: Focusing on Shimotsuki-e for Zhiyi,” was given by Kuo Pei-Chun 郭珮君 (Taiwan University), and highlighted the role of the memorial services held on the anniversary of Zhiyi’s 智顗 (538–598) death, known as Shimotsuki-e 霜月會 in Japan, in legitimizing the Tendai lineage during the Heian 平安 period (794–1185). The next presentation delivered by Kim Sung-Eun 金成恩 (Dongguk University), “Transborder Transmission of Buddhism Based on Sino-centric Ideologies: Increased Sinification of Korean Buddhism in the 17th Century,” focused on the Sino-centric rhetoric shared by both Confucian and Buddhist thinkers during the late Chosŏn 朝鮮 period (1600–1900), and emphasized the uptake in this rhetoric by Buddhist apologists in the seventeenth century in particular. Kim’s argument, however, invited criticism from Shen Weirong, who questioned the need to speak of the increased Sinification of Korean Buddhism when Buddhism in Korea was Sinitic from the very beginning.

Prof. Shen Weirong

The final presentation, titled “Teaching the Transmission of Chinese Buddhism through a Korean Film: Along with the Gods: Two Worlds,” was given by Gloria Chien 簡奕瓴 (Gonzaga University), and illustrated the pedagogical value of the Korean film Along with the Gods, which features the ten kings of hell that originated in Chinese Buddhism during the Tang dynasty, in teaching the complex transmission of Buddhism from China to Korea and its syncretic tendencies in East Asia.

Following the second panel was the opening ceremony for all three conferences. Scholars representing the member universities of the Glorisun Global Network for Buddhist Studies expressed their gratitude for the generous support of the Glorisun Charitable Foundation, and explained the palpable impact the Glorisun Network has had for the study of Buddhism at their respective institutions.

The third and final panel of the first day, titled “Textual Transborder Travelling,” featured seven largely philologically oriented presentations. The panel was chaired by Kim Sung-Eun (Dongguk University) with Kirill Solonin (Renmin University of China) and Wu Weilin 吳蔚琳 (Sun Yat-sen University) serving as discussants. Eviatar Shulman (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) gave the first presentation, titled “What Do We Mean by the Transmission of Buddhist Texts?,” and he questioned the assumption that the “reciters” (Skt. bhāṇaka) who transmitted Buddhist texts, specifically the āgamas, were primarily interested in transmitting a fixed canon of scriptures. Instead, he argued for a more creative conception of the “transmission” of “texts” that captures the flexibility of early Buddhist texts as creative combinations of formulaic expressions. The second presentation by Rev. Madipola Wimalajothi Thero (HKU), titled “The Mahāvihāra’s International Academic Network as Reflected in the Vimativinodanīṭīkā,” explored the international academic character of Mahāvihāra, the famous Sri Lankan monastery, on the basis of evidence from the Vimativinodanīṭīkā, one of three subcommentaries on the Samantapāsādikā—Buddhaghosa’s (fl. ca. 370-450) commentary on the Vinayapiṭaka. The next presentation was given by Baba Norihisa 馬場紀壽 (University of Tokyo), titled “The Four Āgamas as Open Texts,” in which he discussed the formation of a particular discourse from the Ekottarikāgama through comparative research on the basis of texts preserved in Chinese, Sanskrit, and Pāli. The fourth talk, “A Brief Study on a Newly Identified Sanskrit Palm-leaf Manuscript of the Aparimitāyur(jñāna)sūtra,” was delivered by Wang Junqi 王俊淇 (Renmin University of China), who presented a diplomatic edition of an early manuscript of the tantric Aparimitāyur(jñāna)sūtra in proto-Bengali script and illustrated its significant differences from existing editions. The next presentation by Shi Zehui 釋則慧 (Renmin University of China), delivered in Chinese, was titled “續藏本《止觀記中異義》的底本問題 | The Source Text and Associated Issues of the Zhiguan Ji Zhong Yiyi in the Zokuzōkyō.” There, he discussed the philological issues in the present text of the widely circulated Zhiguan jizhong yiyi 止觀記中異義 [Divergent Interpretations in the Commentary to the Great Calming and Contemplation] by Zhanran’s 湛然 (711–782) disciple Daosui 道邃 (ca. 735–811) in the Manji Shinsan Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂續藏經, which is based upon a problematic manuscript stored in the Kyoto University Library. The sixth talk was given by Kirill Solonin (Renmin University of China) in Chinese, and titled “漢傳佛教在中亞的傳播:以西夏文獻為中心 | Sinitic Buddhism among Tanguts.” In this presentation, he discussed the transmission of Huayan 華嚴 and Chan 禪 Buddhism in the Tangut state during the eleventh through thirteenth centuries in a comparative framework to highlight both lesser known features of Sinitic Buddhism during this time as well as the role of Tangut Buddhism in East Asia. The final presentation, also in Chinese, titled “關於菩薩乘靜慮——詞的研究:以《瑜伽師地論・菩薩地》梵文及漢藏譯本為基礎 | Study on Term of Dhyāna: With Reference to Sanskrit Manuscripts of Yogācārabhūmi-Bodhisattvabhūmi and its Chinese-Tibetan Translation,” was given by Shi Jizhao 釋寂肇 (White Horse Monastery of Luoyang). There, he illustrated the procedure for the cultivation of dhyāna (meditative absoprtion) as contained in the Bodhisattvabhūmi through a comparative analysis of the Sanskrit manuscripts and its Chinese and Tibetan translations.

DAY 2 (AUGUST 11)

The first panel of the second day, “Transcultural Transmission and Transformation of Thoughts,” was chaired by Jens Reinke (University of the West), with Zhao Dinghua 趙錠華 (Hong Kong Chu Hai College), Kuo Pei-Chun (Taiwan University), and Li Chih-Hung 李志鴻 (Hong Kong Shue Yan University) serving as discussants. Li Can 李燦 (Beijing Foreign Studies University) delivered the first presentation in Chinese, titled “「首楞經」概念在中國的興起嬗變:一個佛教術語從印度到中國的跨語際旅行 | Rise and Transformation of the Concept of Śūraṃgama in China: Cross-Linguistic Travel of a Buddhist Term, from India to China,” in which he focused on the Chinese assimilation of the notion of śūraṃgama (Ch. shoulengyan 首楞嚴) inherited from India and Central Asia. The second presentation given by Wu Weilin (Sun Yat-sen University) in Chinese, titled “四種夢的解析:律宗吸収化用上座部概念的例證 | An Investigation of Four Sorts of Dreams: Evidence for the Variation of a Theravādin Concept in Vinaya School Works,” dealt with the discrepancies between the varieties of dreams recorded in Buddhaghosa’s commentary on the Theravāda Vinaya, the Samantapāsādikā, and the parallel Chinese version, the Shanjianlü piposha 善見律毗婆沙 as interpreted by several Tang and Song Chinese exegetes.

Prof. Wu Weilin

The third paper, also in Chinese, presented by Li Wei 李薇 (Suzhou University) and titled “玄奘一門對《俱舍論》的闡釋特色 | Characteristics of the Interpretation of Abhidharma-kośa-bhāṣya in Xuanzang’s Lineage,” examined how Xuanzang’s disciples interpreted the jiepin 界品 chapter of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and provided comparative contexts by juxtaposing their annotations to the Sanskrit commentaries by Yaśomitra 稱友 (fl. ca. sixth century) and Sthiramati 安慧 (475–555). The next presentation, given in English, was delivered by Jackson Macor (University of California, Berkeley), and titled “The Three Truths as Madhyamaka Exegesis: Zhiyi and His Role in Chinese Buddhism,” in which he argued based upon a re-evaluation of verse 24.18 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā of Nāgārjuna 龍樹 (ca. 150–250) that the notion of the Three Truths (Ch. sandi 三諦) developed in Tiantai Buddhism does not represent a major departure from Indian Madhyamaka, but rather functions as a sound exegesis of the Indic materials Zhiyi was consulting. The fifth and final talk, “The Early Institutionalization of Buddhism: A Study on Key Terminology in the Aśokan ‘Schism Edict(s),’” was delivered by Michael Cavayero (Peking University) who examined the earliest written record of Buddhist monastic institutions, which dealt with the prohibition against conflict within the Sangha(Skt. saṅghabheda), and the key terms involved in these early documents.

Prof. Michael Cavayero

The second panel of the morning, “Tubo and Turfan,” was chaired by Ester Bianchi (University of Perugia) with Wang Junqi 王俊淇 (Renmin University of China) acting as the discussant. Shen Weirong (Tsinghua University) presented his talk first, titled “The Cult and Yogic Practices of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara within Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism: A Comparative Study,” where he examined the cultic and yogic practices surrounding Avalokiteśvara in Tibetan and Chinese sources. Based on their striking similarities, Shen argued to do away with the artificial barriers that separate Indo-Tibetan and East Asian Buddhism, and to instead treat the entirety of Buddhism in Asia as a holistic development across time. The second paper, presented in Chinese by Yang Zhiguo 楊志國 (Fudan University) and titled “‘金瓶掣簽’下的噶舉派活佛轉世制度 | The Reincarnation System of the Living Buddha of the Kagyu-Sect under the ‘Golden Vase Lottery,’” illustrated the details of the reincarnation system instituted in the Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism during the Qing 清 (1644–1911) dynasty on the basis of manuscripts at the Pelpung Temple, other archival resources, and biographical sources. Drukgyel Tsering (HKU) delivered the third talk of the panel in English, titled “A Preliminary Report on Pa tsob Lo tsa ba’s Newly Unearned Manuscript: Pa tsob lo tsa pa’s Reply to Zhang sha ra pa’s Questions Regarding the Meaning of Madhyamaka,” in which he presented his preliminary findings on a new manuscript containing a text attributed to Pa tsob lo tsa ba (ca. 1055–1145), a pivotal figuring in the history of Tibetan Buddhism who translated and commented upon important works by Nāgārjuna and Candrakīrti 月稱 (ca. 600–650), and examined how Pa tsob lo tsa ba adapted Indian Madhyamaka to suit the Tibetan Buddhist program of gradual practice. The final presentation, “論吐魯番文獻中佛教社會生活史料的「中國化」之路 ——以出土文獻的整理,價値及運用為中心 | Research on the Collation, Value and Application of Historical Materials about Buddhist Social Life in Unearthed Turpan Texts,” was given by Zhang Chongzhou 張重洲 (Tsinghua University) in Chinese, in which he focused on the value of texts from Turpan for reconstructing both the local history of Buddhism as well as its relationship to China and other civilizations.

The third panel, “See Far and Hear Deep: Artistic Amplification,” was chaired by Gloria Chien (Gonzaga University) with Michael Cavayero (Peking University) and Sun Yinggang (Zhejiang University) serving as discussants. The panel began with a presentation in Chinese by Qiu Xiaoyun 裘瀟雲 (Peking University) titled “印度、中亞與漢地的涅槃圖像藝術變遷 | Artistic Transformation of the Nirvana Images in India, Central Asia and China,” in which she examined the Buddha’s lying position in three images in the Yungang caves in juxtaposition with examples from Central Asia and textual descriptions. The second paper delivered by Ashwini Lakshminarayanan (École française d’Extrême-Orient) was titled “Musical Processions in Gandhara and Kucha,” in which she examined artistic representations of musical processions as a means to discern the nature of their transmission in Central Asia.

Dr. Ashwini Lakshminarayanan

The next presentation in Chinese by Wang Lina 王麗娜 (National Library of China), titled “佛教的音聲信仰傳統——以漢譯部派佛典中諦語和咒願為研究中心 | Musical Voice Belief in Buddhism: A Study Centered on Saccavacana and Verses of Vows of Sectarian Buddhist Scriptures in Chinese Version,” focused on the various attitudes toward saccavacana (sayings of truth) in the various Vinaya lineages in Indian Buddhism and their evolution in Mahāyāna and tantric Buddhism. Ma De 馬德 (Dunhuang Academy/Mount Kuaiji Institute of Advanced Research on Buddhism) gave the fourth presentation in Chinese, titled “敦煌莫高窟第205窟‘新東方三聖’壁畫小議 | A Discussion on the Mural ‘New Three Saints of the East’ in Cave 205 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang,” in which he presented the novel triad of Bhaiṣajyaguru, Avalokiteśvara, and Kṣitigarbha found in Mogao Cave 205 as reflecting the social and practical aspirations of artists and donors. The final presentation of the panel was given in English by Wu Xiaolu (Joy) 吳曉璐 (Harvard University), titled “Singing into the Afterlife: The Transformation of the Kalaviṅka in Chinese Buddhist Art,” where she traced the evolution of the mythical kalaviṅka bird that featured in Indian Buddhist scriptures as it took on a humanoid appearance in Chinese art forms during the Tang dynasty.

The fourth panel of the day was split into two concurrent panels, the first of which was titled “Transmission of Buddhist Practices: Meditation, Vinaya and Rituals,” and was chaired by Shi Jizhao (White Horse Monastery of Luoyang) with Li Can (Beijing Foreign Studies University) as discussant. The first presentation, “從印度禪到中國禪嬗變一側面——中國早期習禪者論考 | A Partial View of the Transition from Indian to Chinese Dhyāna: A Study on Early Meditation Practitioners in China,” was given in Chinese by Shi Tongran 釋通然 (Peking University), in which he analyzed meditation practices in China prior to the advent of Chan Buddhism. The next presentation, also in Chinese, given by Chen Zhiyuan 陳志遠 (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) and titled “中古佛教寺院的亡僧遺物清單——解讀《量處輕重儀》| A Detailed List of Properties of the Deceased Monks in Medieval Buddhist Monasteries: Re-examining the Standards for Handling the Light and Heavy Properties,” detailed the daily life of monastics on the basis of Dunhuang manuscript editions of Daoxuan’s Liangchu qingzhong yi 量處輕重儀 [Standards for Handling the Light and Heavy Properties], which preserved earlier editions of the text.

Dr. Chen Zhiyuan

The third presentation delivered by Shi Hongxiang 釋宏祥 (HKU) in English, “An Exploration on the Ideologies of Fazhao’s Ritual Manual,” analyzed the sources of Fazhao’s 法照 (d.u.) thought as reflected in the Jingtu wuhui nianfo songjing guanxingyi 淨土五會念佛誦經觀行儀 [Ritual Manual of the Five-Tempo Intonation of the Name of the Buddha for Recitation of Scripture and Contemplation of Pure Land]. The final presentation in Chinese, “佛教類書的編撰與佛教中國化研究——以《釋氏六帖》為重點 | The Research on Compilation of Buddhist Leishu and the Sinicization of Buddhism: Focusing on Shishi Liutie,” was given by Zhang Xueqi 張雪琪 (Nanking University), in which she discussed the history and reception of the Shishi liutie 釋氏六帖 [Six Books of the Śākya Clan] in East Asia.

The second of the concurrent panels was chaired by Ngar-sze Lau 劉雅詩 (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) with Jackson Macor (University of California, Berkeley) and Shi Daowu (Mount Kuaiji Institute of Advanced Research on Buddhism) serving as discussants, and was titled “Buddhification or Sinification?: Buddhist Elements in Chinese Political Institutionalization.” The first presentation by Tan Yingxian 談穎嫻 (Hebrew University of Jerusalem), titled “The Buddhist Empowerment of Daxingcheng: Emperor Wen’s Relocation of Monks and its Religiopolitical Significance,” examined how the first Sui emperor, Emperor Wen 隋文帝 (r. 581–604), consolidated religious authority in the newly constructed capital of Daxingcheng 大興城 as part of his program of utilizing Buddhism as a means of political reunification.

Ms. Tan Yingxian (Ph.D. Student)

The second presentation in Chinese, “北宋前期的王權,舍利與神聖空間:從唐宋變革期的觀察 | Kingship, Relics, and Sacred Space in the Early Period of the Northern Song: A Perspective from Tang-Song Transformation,” given by Li Chih-Hung (Hong Kong Shue Yan University) in Chinese similarly detailed how the emperors of the Norther Song 北宋 (960–1126) utilized the cult of Buddhist relics to establish their authority as Buddhist kings. The next presentation also in Chinese was delivered by Pei Changchun (Shangdong Normal University) and titled “五代時期仁王會小考 | A Humane Kings Convocation Held in the Zhongxing Palace: A New Study of the Scriptures Preached on the Holy Emperor’s Birthday at the Zhongxing Palace in the Fourth Year of the Changxing Era (933 AD),” in which she analyzed a Buddhist popular sermon preserved in P.3808 and how it sheds light on the Humane Kings Convocation (renwang hui 仁王會). Ma Xi 馬熙 (Nankai University) gave the final talk of the panel, titled “《不空表制集》‘無名僧’發覆——重審唐代佛教私度史 | ‘Unregistered Monks’ (Wuming seng 無名僧) in the Collected Documents of Amoghavajra: A Re-examination on the History of Private Ordinations in the Tang Dynasty,” in which he examined the categories of “unregistered monks” and those who underwent “private ordination” (sidu 私度), and argued that the prior recorded in the Collected Documents of Amoghavajra (Bukong biaozhiji 不空表制集) refers to the latter as found in official documents from the Tang.

The final panel of the conference, titled “Globalization by Localization,” was chaired by Eviatar Shulman (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) with David Wank (Sophia University) and Jens Reinke (University of the West) serving as discussants. The first talk was given by Ester Bianchi (University of Perugia) and titled “Glocalizing Buddhism: The Huayisi 華義寺, a Taiwanese Nunnery for Mainland Chinese in Italy,” in which she presented her preliminary research on the Huayisi 華義寺 in Rome, Italy and its affiliations with monastic institutions in both Mainland China and Taiwan as well as other Buddhist institutions in Italy. The next presentation by Chiu Tzu-lung 邱子倫 (Chengchi University), titled “Contested Status and Problematizing Identity: Chinese Mahayana Buddhism in Transnational Contexts in Myanmar,” examined the strategies Chinese monastics have adopted in modern Myanmar, where Theravāda Buddhism is dominant. The third paper delivered by Jens Reinke (University of the West) and titled “Chinese American Mahayana?: The Emergence of a Global Buddhist Space in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area,” detailed the diverse presence of Chinese Buddhist temples in the San Gabriel Valley east of Los Angeles, California. The final presentation, “Fitting the Needs of Spiritual Diversity: Developing Transnational Buddhist Meditation Event ‘Zen Meditation with Thousands’ in Hong Kong,” was given by Ngar-sze Lau (The Chinese University of Hong Kong), in which she examined how the public event “Thousand people Zen meditation” (qianren chanxiu 千人禪修) has been used in contemporary Hong Kong as a means of promoting social harmony.

In summation, the conference “Sinification, Globalization or Glocalization?: Paradigm Shifts in the Study of Transmission and Transformation of Buddhism in Asia and Beyond” as part of the forum “Beyond Civilizational Clash: Buddhist Perspectives on the Coalescence of Human Civilizations” presented ample opportunities for scholars from Asia, Europe, and North America to get a taste of each other’s research and scholarly methods. The diversity of research topics along with the fluid bilingualism of the event, however, was not without issue. As Barend ter Haar (Hamburg University) remarked during the closing ceremony, Western scholars, some of whom may not enjoy perfect felicity with Chinese, tended to listen only to those presentations in English while Chinese scholars, some of whom may not be fluent in English, often observed only those presentations given in Chinese. Despite the obvious challenges however, the event was a stimulating venue for international collaboration and exchange for the study of Chinese Buddhism and beyond, and served as an excellent opportunity to broaden the horizons of academic research for all scholars involved.

Jackson Macor received a B.A. in South Asian Languages and Civilizations (2017) and an M.A. in Divinity (2020) from the University of Chicago, both supplemented by language study in India and Japan. His research interests include doctrinal developments in Chinese Buddhism during the Sui and early Tang, in particular the writings of the Sanlun (Three Treatises) exegete Jizang.

Source: CJBS News Blog