Click here to return to main conference page.

1. 佛教價值觀與經濟學

By 編輯精選. February 21, 2019.

佛陀早於2500多年前,已教導弟子與財富管理相關的概念,當中包括如何契應佛法,正確地積聚和運用財富。近年,佛教價值觀與經濟學的跨學科研究不斷發展,備受重視。在全球市場經濟的不斷發展中,我們於道德及社會環境等不同層面,面對種種挑戰。

有見及此,香港大學佛學研究中心聯同歐洲經濟及社會中的精神價值研究學院(European Spirituality in Economics and Society Institute),以「佛教價值觀與經濟學:投資可持續發展的未來」為主題,於2019年4月13至14日假香港大學舉行一連兩天的佛教經濟學國際會議。

為期兩天的會議將舉行18場講座和論文發表、4場研討會及3場工作坊。18位國際和本地知名的學者和專家獲邀出席會議,並發表論文及演講。講者包括加利福尼亞大學柏克萊分校經濟學教授Clair Brown教授、布達佩斯科維努斯大學商業道德中心教授兼總監Laszlo Zsolnai教授、不丹國民幸福指數研究中心總監Dasho Karma Ura、挪威卑爾根挪威經濟學院戰略與管理系商業道德教授Knut J. Ims教授等。

不少佛教價值觀與經濟學跨學科研究的著名學者,以及來自私人企業、公共事業和非牟利團體的專業人士,亦會參與會議並主持研討會和工作坊,分享他們的研究成果和經驗,共同探討如何把佛教價值觀融入到經濟發展中。

主流價值觀認為,企業以追求利潤最大化為目的,地方發展

下月中舉行的佛教經濟學會議,18位知名專家學者將解讀

2. The University of Hong Kong hosts International Buddhist Values and Economics Conference

From 13-14 April the Center of Buddhist Studies (CBS) at The University of Hong Kong (HKU) hosted an international conference titled, “Buddhist Values and Economics: Investing in a Sustainable Future.” The conference, sponsored by GS Charity Foundation Limited, drew speakers and workshop presenters from across North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. The conference addressed a wide range of perspectives, from academic analysis of early Buddhist texts and interpretations of wealth to contemporary applications of Buddhist values for business leaders and investors.

The co-organizer of the conference was the European Spirituality in Economics and Society (SPES) Institute, under the Presidency of Professor Laszlo Zsolnai. The institute, founded in 2004 in Leuven, Belgium, aims to foster greater international understanding and practice of spirituality in economic and social life.

In his introductory keynote address Saturday morning, Prof. Richard Payne of the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley, California, noted that historically, Buddhism has existed in a context of exchange economy. Modern capitalism, he continued, with its ideals of individualism and rational choice are foreign to Buddhism, since the latter rests on the premise that people are driven instead by varying degrees of ignorance. Charles Lief, President of Naropa University, delivered a paper which was more optimistic about integrating Buddhist ideas into contemporary business, citing the example of the large corporate insurance company Aetna, which has successfully implemented a mindfulness program for its employees.

Prof. Hendrik Opdebeek then spoke of the urgency of addressing economic concerns with an ideal of “enough” rather than a proliferation of consumer goods; and Prof. Knut Ims offered the example of Deep Ecology pioneer Arne Naess as a way for Buddhists to reflect on ideals of prosperity and flourishing and potentially challenge contemporary consumerist ideals.

Presenters and moderators presented with gifts from the Center of Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong. Image courtesy of Yan Chan

In a second keynote on Saturday, Dasho Karma Ura, President of the Centre for Bhutan Studies & Gross National Happiness, spoke of the exploitation of labor as a form of “taking what is not given,” the avoidance of which is the second lay Buddhist precept. Papers continued through the afternoon exploring Buddhist perspectives on material wealth by Prof. Ven. Jing Yin and Dr. Guang Xing of the University of Hong Kong.

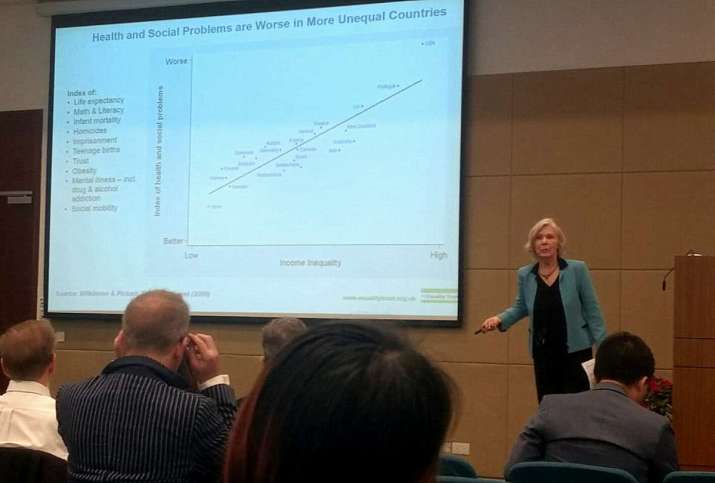

University of California, Berkeley economist, Prof. Clair Brown, offered the keynote address on Sunday morning, pointing out ties between wasteful economic choices and our current ecological crisis. She noted the correlation between income inequality and unhappiness around the world, using a chart showing that the United States of America has uniquely high levels of both. Her call was for citizens to realize that we are all in this together and that governments must choose a more sustainable path forward for the sake of future generations.

Professor Clair Brown shows the correlation between income inequality and increasing health and social problems among various countries. Image courtesy of the author

Dr. Ernest Chi-Hin Ng speaking before the audience at The University of Hong Kong Sunday. Image courtesy of the author

Dr. Georgios Halkias and Dr. G. A. Somaratne of the University of Hong Kong offered historical accounts of Buddhist practice and belief around wealth, Dr. Somaratne focusing on early Buddhism and Dr. Halkias covering Tibetan ritual practices for prosperity. Dr. Ernest Ng, Buddhistdoor columnist and CEO of the Buddhist NGO Tung Lin Kok Yuen, offered a paper placing Buddhist economics in the context of the varied Western perspectives.

Concurrent workshops explored, on Day One, topics such as integrating transmundane Buddhist wisdom with contemporary corporate management strategy, led by business administration scholar and senior HKSAR government directorate Dr. Anthony Lok, leadership excellence and organizational transformation, led by Julia Culen and Christian Mayhofer, and a Mahayana Buddhist approach to stress management, led by Ven. Sik Hin Hung and Bonnie Wu. On Day Two, the workshops explored social values in entrepreneurship with Francis Ngai Wah-sing, founder of Social Ventures Hong Kong and David Yeung, founder of Green Monday, and sustainable finance and banking with Ven. Hin Hung, Andrew Fung, CFO of Henderson Land, and George Leung, advisor to the deputy chairman and chief executive of HSBC.

A closing workshop on Day Two, led by Debra Tan, Director of China Water Risk, emphasized the importance of the Tibetan plateau, often refered to as the “third Pole” because of the amount of fresh water stored there in glaciers. Global warming, Tan warned, is effecting the plateau at twice the average rate of the planet, which will lead to drastic reduction in existing glaciers, effecting the fresh water supplies of over a billion people living in the region.

Buddhistdoor Global Senior Writer Raymond Lam moderating a workshop on social values in entrepreneurship. Image courtesy of the author

Buddhistdoor Global Senior Writer Raymond Lam moderating a workshop on social values in entrepreneurship. Image courtesy of the author

The conference showcased a wide variety of perspectives in addition to those discussed here, across both geography and varied disciplines in both academia and the business world. In the closing session, Ven. Phra Dr. Anil Sayka, Rector of the World Buddhist University in Thailand, noted that the very term “sustainable” is derived from the Latin sustinere meaning “to hold up, to support or bear” and this is nearly identical to the root meaning of the Buddhist term “dharma,” which is “to hold firmly, support.” Thus, he suggested, in our promotion of sustainable economic ideals, we are in turn promoting and promulgating the Dharma.

Presenters receive gifts at the opening of the Buddhist Values and Economics conference. Image courtesy of Raymond Lam

3. Buddhist Economics: a practical approach to master our global crisis

By Julia Culen. August 16, 2019.

In this post am offering my personal takeaways in 10 chapters from a Conference on Buddhist Values and Ethics in Economy we attended and spoke at in Hong Kong in April 2019. The conference was organized by the Centre of Buddhist Studies of HKU and the European SPES Institute. This two-day conference was an impressive convention of academics, spiritual leaders, researchers, politicians, entrepreneurs, wealthy donors, impact investors, financial- market experts and consultants sharing their current state of insights, ideas and thoughts. All videos are available here.

One personal note at the beginning: I don’t believe Buddhist values and economics hurt the economy and business. On the contrary, but this very place where it should be expressed: in our daily personal lives in businesses and companies and in national economics and political action. Buddhism is powerful only, when applied to the very heart of our everyday lives, business and society.

1. What is Buddhist Economics?

While Buddhist Economics as a field of research may still be new to many, it has grown over the last few decades. The term Buddhist Economics is believed to have been coined by E. F. Schumacher in his pioneering 1970s work, Small is Beautiful. Inspired by Buddhist philosophy, Schumacher believed that the economy should serve society ”as if people mattered.”

Schumacher foresaw the problems that come with excessive reliance on the growth of income, especially overwork and dwindling resources. He argued for a system that valued individual character development and human liberation over-attachment to material goods. In Schumacher’s view, the goal of Buddhist Economics is “the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption” (Buddhist Economics, Clair Brown, p. xiii).

Buddhist Economics is the integration of key Buddhist values and ethics (such as non-violence, compassion, love and wisdom) with Economics – on a global, regional and individual level.

”Compassion and mindfulness can make our businesses a pleasure for ourselves and a gift for our employees and for the world.” Thich Nhat Hanh, the world-famous Zen teacher and founder of Mindfulness

2. What is the main goal of Buddhist Economics?

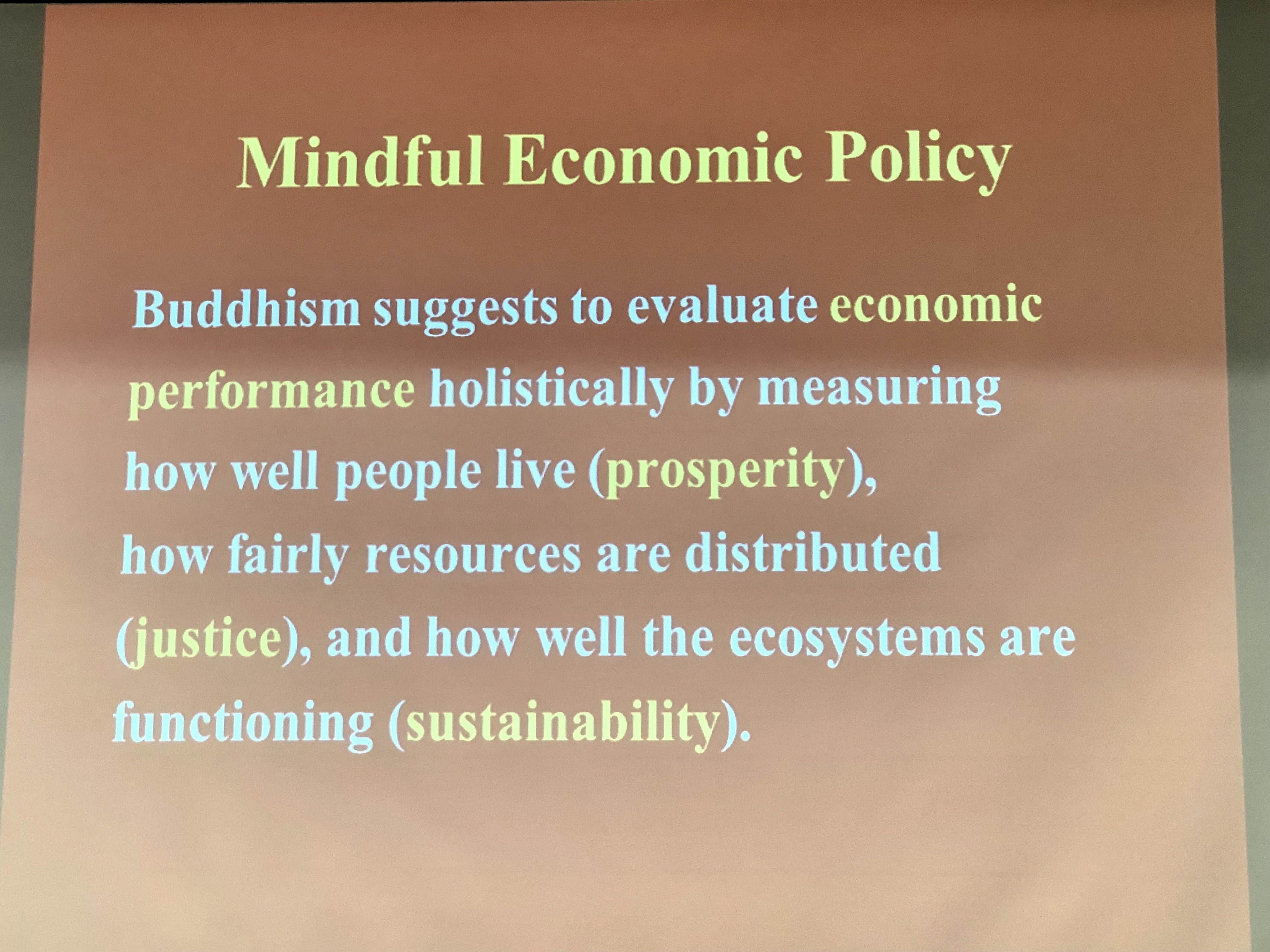

Buddhist Economics aims to establish shared, sustainable prosperity on a global level.

- Shared means that everyone is included; it can be measured by how fairly resources are distributed.

- A sustainable economic system does not rely on exploitation, destruction and extinction to fuel its growth but rather creates beneficial outcomes for people and the environment. It is measured by how well ecosystems are functioning.

- Prosperity indicates how well people live, from the focus on economic growth and insatiable needs to buen vivir: the good life based on the communion of humans and nature.

”In Buddhist Economics, taking care of our human spirit is part of our lifestyle.” – Clair Brown, Professor of Economics, University of California Berkeley

3. What are key challenges Buddhist Economics addresses?

- Global warming: the threat of environmental collapse

- Income inequality: vast economic disparities with opulent living for a few, comfortable living for many, and deprivation with suffering for most

Both of these challenges are interrelated and profoundly influenced by economics.

Inequality and CO2 emissions go together: Rich countries and people are big polluters, while inequality is a source of suffering. In 2014, less than 1% of people owned 48% of global wealth while the bottom 80% shared only 5.5% of global wealth. (source:Buddhist Economics, Clair Brown) In addition, people feel worse off as inequality grows. The problem of inequality is nailed down with this quote from Zsolnai, Lud, and Opdebeeck: “The world is not divided between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ but between a majority that do not have enough and a minority that has too much.”

It is a fact that countries choose their level of inequality and their carbon footprint. It is not just a matter of taking away from the rich and giving to the poor but rather of defeating the root cause and the legislation which leads to inequality in the first place. While neoliberals promote “free” markets (meaning little governmental interference and few regulations), there is no such thing as a “free” market, since the more you have, the more power you have. We all know the dynamics of monopoly; the rich get richer and the poor people get poorer. This is ultimately where free markets lead, unless there is a higher power, called politics.

The guiding questions are manifold:

- How can we create an economic system that avoids increasing wealth inequality, environmental degradation and epidemic unhappiness despite rising GDP?

- How can market economics truly contribute to the welfare and happiness of human beings?

- How can we address economics not only on a technical, scientific level but also on a spiritual, mental and cultural level?

- What are the key activities to be carried out on an individual and collective basis?

- How can we move from a paradigm of growth (at the expense of individual physical and mental wellness, financial system stability and the ecological system) to a paradigm of prosperity?

4. What are the key ethics and values of Buddhism?

Buddhism is a spiritual wisdom tradition and not a religion, as there is no God involved. The underlying key question and goal of Buddhism is just one question:

- Why do all sentient beings suffer, and how can we reduce suffering?

Spiritual and contemplative practices such as meditation are meant to help clear the mind and cut through illusions (including the idea of a separate self) in order to take wise action in the midst of life. The purpose of monks and monasteries and teachings is to cultivate this wisdom, not to keep it away from people.

The key assumption is that most of our suffering is self-inflicted and thus can be relieved by ourself.It is an approach of self-empowerment rather than the belief in a higher power we depend on for better or worse.

Here are some of the related teachings and principles I find most relevant:

- All human beings suffer. The main sources of suffering are:

- Ignorance: the illusion of a separate self

- Greed: seeking objects, endless wants and blind craving for things

- Hatred: the lack of compassion

- Interdependence with each other and with nature: “Everything is connected to everything else. There is one ecosphere for all living organisms (sentient beings) and what affects one, affects all.” – Barry Commoner, founder of modern ecology. Inter-Being is also used in this context.

- Impermanence: Everything changes. Attachment causes suffering, as nothing stays at it is.

- Acceptance: Seeing things as they are and not as we wish them to be in a non-judgmental way. Not to be mistaken with resignation. Rather the precondition to take effective action.

- Most important values and ethics in behavior: generosity, non-violence, compassion, kindness, contentment, wisdom and mindfulness. The golden rule comes down to treating others in the way you want to be treated.

5. What is the difference between Western Economics and Buddhist Economics?

This slide was shown during the Buddhist Economics conference in April, and it summarizes the key differences nicely:

Key Assumptions of Western Economics

- Maximizing framework focused on maximizing profits, desires, markets, instrumental use and self-interest.

- Economy of dissatisfaction: Desires are not meant to be satisfied but rather to be created, inflated and cultivated. Use of the endlessness of human wants.Value of things = monetary price. The value of everything, even damage to nature or life itself, is expressed in a “price” or money.Because Gross Domestic Product uses only income to measure economic growth, income has become a country’s primary focus.

- Dystopian conception of humanity (Menschenbild): People’s strongest motivation is economic greed to increase material wealth in a manner reflecting survival of the fittest, natural selection and competition.

- Paradigm of technical and scientific progress dominates and suppresses metaphysical, human and spiritual dimensions

- Neoliberalism/capitalism: Inequality is required in order to provide incentives for people to work hard and be rewarded for their contributions to the economy. Social security and other social nets will spoil people. Hardship is an intended tool of incentive. Money rules the world.

- Means justify the end. Even if they are ruthless and violent (war). Paradigm of separation: Since we are all different and separate, suffering of people far away is none of my concern. Self-optimization at the cost of others is acceptable, if not necessary. Competition: Competitive markets ensure the best possible outcome, even if some people are still starving. Aid interferes with global markets and might support corruption. Thus, intolerable injustice is tolerated. Materialistic possessions lead to well-being, safety, happiness and status. Exploitation: The environment and foreign countries are regarded as resources for rich countries to dominate and exploit. Economy is a zero-sum game: Your gain is my loss, so it is a “you OR me world” instead of a “you AND me world.” Creation of win-lose situations. Profits are individualized, costs are distributed to the society (environmental damage, bail-outs…).

Key Assumptions of Buddhist Economics

- Minimizing framework focused on minimizing suffering, desires, violence, instrumental use and self-interest.

- Less is more: As motivation is intrinsic rather than materialistic, low material consumption and a simple lifestyle open the mind for spiritual goods. The essence of civilization is not in the multiplication of wants but in the purification of human character.

- Sufficiency: Economy of enough (how much is enough?)

- Happiness from giving, not having: Eudaimonic (intrinsic) happiness comes from helping others, having good relationships, contributing to the community and caring for the planet. In contrast, since hedonic happiness stems from consuming and buying, it does not last long (assuming that basic needs are met). Buddhist Economy does not promote poverty!

- Wealth is inexhaustible and can be measured in inner dimensions such as love, compassion and wisdom. It can be increased by cultivation and spiritual practices. No outer wealth is needed for this (just enough). Outer wealth is also fine as long as we do not become attached to possessions, and we share our riches with others.

- A digression is to consider why happiness does not increase with (national) income. The reason is known as the Easterlin Paradox: Once basic needs are met, average national happiness tends to remain the same, while average per capita national income grows. This is due to people’s adaptability to situations or events, both positive and negative. In addition, people strongly link avoiding a loss to acquiring a gain; economists call this “loss aversion.” Even if we enjoy a good event or outcome, we soon adapt to it and return to our baseline sense of well-being.

- Wealth is inexhaustible and can be measured in inner dimensions such as love, compassion and wisdom. It can be increased by cultivation and spiritual practices. No outer wealth is needed for this (just enough). Outer wealth is also fine as long as we do not become attached to possessions, and we share our riches with others.

- The means condition the end: Good actions lead to good results.

- Key values are: (1) Minimize suffering (2) Simplify desires (3) Practice non-violence (4) Genuine care and (5) Generosity.

- Value creation: Production is truly justified only when the value of the thing produced outweighs the value of that which is destroyed.

- Total cost allocation: The full price of all resources used is included in the market prices for all goods and services. The price of gas includes a pollution tax, often called a carbon tax, equal to the cost to society of the damage done to the environment.

- The economic distinction between individual behavior and national outcomes dissolves, because individual well-being is no longer distinct from societal well-being.

- Philosophy of win-win: When rich people share with poor people, the rich will still have more than enough and the poor will be much better off, will be able to participate in society, buy goods and services. The wellbeing of both improves. Every person and the society as a whole win (vs. the zero-sum game of western economics).

- Beneficial action

- Beneficial technology:Adapted forms of technology that do not undermine human happiness

- Respecting the physical limits on natural capital:Man-made capital and natural capital are not the same; physical limits on natural capital exist, and critical ecosystems must be preserved. These limitations impose strict constraints on economic activity.

6. What is the scientific foundation of Buddhist Economics?

The 2019 “Buddhist Economics” Conference in Hong Kong gathered contemporary researchers and academics in this field. They included Clair Brown, who taught Buddhist Economics at UC Berkeley and is the author of Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science,and Prof. Richard Payne, editor of the essay collection How Much is Enough?: Buddhism, Consumerism, and the Human Environment. Also attending were representatives from Bhutan to present about Gross National Happiness (GNH); in addition, the venerable Dr. Jing Yin (淨因法師), abbot of the Po Lin Monastery in Hong Kong and former Director of the Centre of Buddhist Studies, gave a presentation about the Buddhist Perspective on Wealth. Prof. Laszlo Zsolnai, a Hungarian economist influenced by E. F. Schumacher and who has published books on Buddhist Economics since 2006, was invited but could not attend due to health issues.

In addition to including scholarly topics, the conference held panels on the practical aspects of integrating values into businesses. Speakers included Jed Emerson and Annie Chen (influential in impact investing and sustainable finance), David Yeung from Green Monday and Francis Ngai from Social Ventures Hong Kong (iconic figures in the area of social entrepreneurship), and Andrew Fung, George Leung and Ernest Ng (very successful in their banking and finance careers).

In particular, Clair Brown delivered the scientific research and numbers proving that Buddhist Economics is real and actually more effective and profitable in a holistic sense than the “Western” approach. Western Economics is compared to Buddhist Economics, because western countries are the main polluters. CO2 pollution does not reflect population but rather standard of living: Rich western countries are the main polluters, use the most resources by far, and consume the most. The numbers are impressive.

7. Why would anyone address hard problems, such as the economy and environmental collapse, with a spiritual philosophy?

During the last 100 years, we have seen a shift from a spirituality-oriented culture of frugality into a materialistic culture supported by modern media.

“I used to think that top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change. I thought that thirty years of good science could address these problems. I was wrong.

The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy; to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.” – James Gustave Speth, American environmental lawyer and advocate, 2013

We cannot solve our problems with the same mindset that created them, and Buddhist Economics invites us to reflect on and transform the basic beliefs and assumptions upon which our current economic system is based. As Speth points out, the environmental crisis is the result of our state of mind and culture.

Harmful behavior and undesirable outcomes can be seen as the manifested result of inner states of anxiety, aggression, discontentment, greed, hate, fear and desperation.

Addressing environmental destruction and economic dysfunction requires addressing the spiritual and psychological dimensions and the – mostly unmet – human need for connection, safety and personal development.

Emotional factors such as fear and desire are more powerful than reason, driving us to our worst economic excesses of greed, overconsumption and materialism while damaging our societies and ravaging our environment. The science of economics adopts a rational approach, but the issues of fear and the emotional need for security are far more basic.

“The theoretical models remain rational solutions to largely irrational problems.” – Venerable Prayudh Payutto, Buddhist monk

Beware of Spiritual Materialism

We can deceive ourselves into thinking we are developing spiritually when instead we are strengthening our egocentricity through spiritual techniques. This fundamental distortion may be referred to as spiritual materialism.

“There are numerous sidetracks which lead to a distorted, ego-centered version of spirituality.” – Chögyam Trungpa, Tibetan Buddhist, founder of Naropa University

We can create a spiritual ego, by saying, “I am more spiritual than you are! I am more conscious and self-aware than you.”Judgment, comparison and depreciation get in the way and play out counter-productively.

“Our collective compassion, mindfulness and concentration nourishes us, but it also can help to reestablish the Earth’s equilibrium and restore balance. Together, we can bring about real transformation for ourselves and for the world.” -Thich Nhat Hanh

8. Are there real-life examples?

- Circular Economy: prevention of the exhaustion of scarce resources, recycling of waste and use of energy sources such as wind and sun.

- Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP), adopted by Thailand in 1974: Three interrelated components and two underlying conditions are central to SEP’s application. The three components are reasonableness(or wisdom), moderation, and prudence. Two essential underlying conditions are knowledge and morality. In contrast to the concept that the primary duty of a company is to maximize profits for the benefit of shareholders, SEP emphasizes maximizing the interests of all stakeholders and having a greater focus on long-term profitability as opposed to short-term success.[1]:26-27

The Chaipattana Foundation says that sufficiency economy is “…a method of development based on moderation, prudence, and social immunity, one that uses knowledge and virtue as guidelines in living.” Source: Wikipedia

- Bhutan introduced the GNH (Gross National Happiness) Index instead of GDP to measure the nation’s prosperity and well-being. The GNH sets up sufficiency benchmarks, specifying the basics they think everyone should have, in nine important areas of life, including mental and physical health, community vitality and ecological resilience, and uses attainment of sufficiency in these areas to classify people in four groups, from unhappy to extremely happy. Bhutan uses the GHN to focus on policies that ensure everyone is extensively or deeply happy

- Some societies, including Sweden, Finland and Norway, have made child welfare and shared prosperity top priorities. These countries have achieved widespread income quality, with a high standard of living for all. On the contrary, national regulations have increased inequality in many nations: reduction of taxes on income and inheritances, the weakening of labour unions, the meteoric rise of rich financiers following the deregulation of the finance industry, the increased market power of companies as they consolidate. (Buddhist Economics, Clair Brown)

- Economy of Frugality

- Deep ecological thinking: simplicity of means and richness of ends

- Positive Psychology: Simplifiers appear to be happier

- More fun with less stuff

- Consuming less – voluntarily, can improve subjective wellbeing.

9. Who can take action and how?

What each of us can do:

- Consuming less, buying only what you need. Knowing moderation is knowing how much is “just right.” Adopting a simpler lifestyle: Sustainable shared prosperity requires that people in rich countries develop simpler, sustainable lifestyles so that people in poor countries can live comfortably.

- Not harming oneself or other sentient beings (for example, with toxic chemicals, plastics and fossil fuels).

- Not buying cheap products: People in rich countries who buy inexpensive goods made by foreign workers, do harm to those workers who put in long hours in dangerous conditions at very low wages

- Living mindfully with love, compassion and wisdom

- Working together and taking action

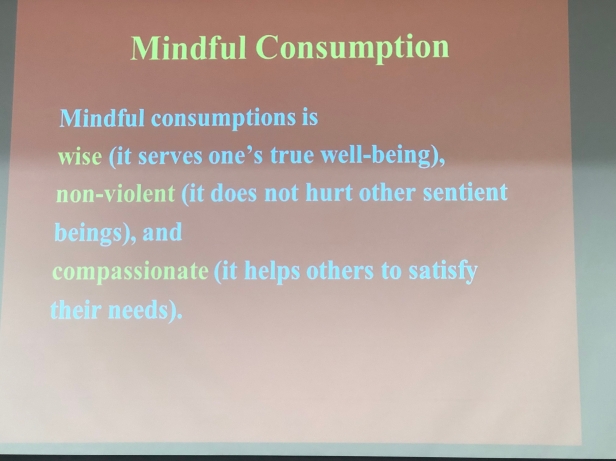

- Mindful consumption is wise (it serves one’s true well-being), non-violent (it does not hurt other sentient beings), and compassionate (it helps others satisfy their needs). An example is buying local, regional products from organic farmers.

- A Buddhist Economy can create a healthier, happier world.

What companies (can) do:

- Patagonia is the perfect place I found to apply Zen philosophy. “Build the best product. Cause no unnecessary harm. Use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis. Repair is a radical act.”

- Mindful, social entrepreneurship: David Yeung, also speaker at the conference, founder of Green Monday and early investor in Beyond Meat Inc., is a true star in promoting sustainable and healthful food with no animals involved. I know him personally, and for me he is one of the most influential and important social entrepreneurs in the best sense, trying to change the system and influence policies, by offering convincing alternatives to traditional meat-eaters.

- Companies can and must align with the goals of sustainability and equality. They can share profits and stop hurting the environment. Of course, there are obvious organizations such as NPOs and social entrepreneurs, but they cannot outweigh the impact of for-profit companies. Each and every organization will have to deal with these issues, if not for the sake of society then for their own survival: Customers, partners and (young) employees will decreasingly accept irresponsible polluters and organizations creating physically or mentally toxic biospheres. Reducing the exorbitant pay of CEOs and other executives could be one step to increasing the pay of average workers so everyone makes a living wage (instead of working poor).

- Buddhist Economists also promote a leadership style that is informed and nourished by wisdom, kindness and compassion. It is not enough to not do harm; it is about creating beneficial outcomes and honoring the opportunities that come with power and possibility.

What politics and societies (can) do

The United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals summarize everything that is to do, but here are some key topics taken from Clair Brown’s book Buddhist Economics.

a. Tax and transfers:

Market regulations that create a sustainable global economy. They provide incentives to support ecosystems and distribute resources equitably. Examples are taxing and regulating carbon and consumption, promoting green technology, sharing wealth (just today I learned, thatUS billionaires even asked to be higher taxed in order to finance climate challenges.)

b. Sustainable agriculture

Industrial agriculture is responsible for emitting up to one-third of global greenhouse gases and its overuse of water and fertilizers devastates rivers, lakes an oceans. Deforestation causes loss of species and changes the weather. Critical ecosystems are destroyed in the rain forests. and so on.

Sustainable agriculture practices that use land and water wisely include using compost, crop rotation to replenish the soil, natural pesticides or biodiversity, raising animal without hormones and antibiotic. Of course this demands a change of lifestyle, or the use of meat substitutes. Measure and transform:

What gets measured gets done. Currently it is GDP for most countries. New measures try a more holistic approach, including well-being, happiness, sustainability and many more.: UN’s Human Development Index (HDI), the Sustainable Development Goals Index (SDGI). Or Bhutans Gross National Happiness (GNH), consisting of many sub-categories.

c. Shared prosperity

Inequality is a choice: Economist Joseph Stiglitz has demonstrated that a country’s inequality is not an inherent outcome of capitalism, but a choice that the country has made through ist national laws and institutions. Government policies shape how people share a country’s resources. Economists are currently developing different systems of how to share prosperity like a guaranteed minimum income, capital endowment to young people, employee ownership and profit sharing, among others

Keeping fossil fuels in the ground!

d. Peace and prosperity

War on terrorism does not seem to work: The outcome i the creation of more terrorism, violence and hatred. Promote non- military solutions: replace war with humanitarian aid, long-term support for political, economic and social progress. Over time the profits from weapons could be shift into profits from beneficial action. (The five largest exporters of weapons are the United States (31%), Russia (27%), China, Germany and French (5%) each. The largest importers are India (15%), Saudi Arabia and China (5%), and then UAE, Pakistan and Australia (4%) each. )

To embrace and practice Buddhist economics, you need courage. Courage to change, courage to protect the environment, courage to promote justice, and courage to live with joy. Clair Brown, Buddhist Economist

10. Personal remarks and thoughts

When I studied International Business Administration in the 1990s, absolutely not once did we discuss the implications and what it means for humans. We were trained how to manage companies and organizations so they would deliver maximum results with minimum resources. Environmental concerns were no issue. Sociology was maybe the only subject area in which the human dimension was shining through. In Economics we calculated curves and discussed fiscal and financial and tariff means to protect and balance the markets. There was actually no critical aspect in discussing a dehumanized approach to economics. Profits were the religion, success was key. Personal success the goal. By that time I did not even question the basic paradigms, I was not even aware what that all really meant. Today I know better and can use my academic training in a different way.

The idea of a simple life is incredibly appealing to me. I am transforming my personal life too, step by step. Buying less and less (except flowers), traveling by train where possible, avoiding flights (still too many) and growing into vegetarian diet. In my house I avoid the use of chemicals, we create our detergents from natural ingredients (get this book) and avoid toxic people. We grow our own food in the garden, a small contribution. We buy groceries from the producers on farmers markets or from the farmers, which is of course easier when living in the countryside. We use bikes. Small steps.

After the Buddhist Economy conference we thought about what else we could reduce in our life, also in a sense of constructive self-reduction: we cancelled Netflix, Christian retreated from Facebook and I try to control screen time. It is all so little compared to the world problems, but not everyone has to solve everything. It is small simple steps we do, together.

In our consulting work we increasingly address issues like environmental concerns, how employees are treated, fair payment. We are not in the position to lecture clients morally, still we do think life is urgent and with my opportunity to access top management comes a responsibility.

On a global level Christian and I work towards bringing wisdom tradition into the world of business and connecting the dots – which just appear to be separate when you look on a superficial basis. If we look beyond the visible surface, we can see suffering and the spiritual longing for connection, being pacified by consumption, overwork and greed. But actually this is not what people desire deeply and we think we all could bring back natural human connection and compassion and stop harming others and ourselves. Instead we could wake up to how much we already have, how little we actually need on a material basis and start to focus more on our spiritual and human potential. We would all be happier and less destructive.

Instead of turning our bad conscience, guilt and shame for causing harm into aggression and hatred, we could consider ourselves as beings that could actually be beneficial for others and the environment. Dreamers are not the people who imagine a different future, but the people who make us believe we can continue the current path forever. – Julia Culen

P.S.: Christian and I delivered a Workshop on “Personal Mastery, Leadership and Organizational Transformation”, you can find our talk and Post Blog here